If you surf the internet or watch late night television, you are no doubt aware of the close scrutiny robotic surgery is under. Medical experts from reputable institutions have come forward decrying the lack of evidence of clinical effectiveness and added costs of robotic surgery. Legal firms across the USA are actively seeking clients allegedly injured during robotic surgery to initiate class action lawsuits.

If you surf the internet or watch late night television, you are no doubt aware of the close scrutiny robotic surgery is under. Medical experts from reputable institutions have come forward decrying the lack of evidence of clinical effectiveness and added costs of robotic surgery. Legal firms across the USA are actively seeking clients allegedly injured during robotic surgery to initiate class action lawsuits.

While Canadian surgeons are not different from American surgeons in that they are motivated by the same desire, first and foremost, to provide safe and effective care for their patients, it is important to understand the very distinct drivers behind adoption of robotic surgery in Canada and the USA and similarly to separate myth from fact in terms of the evidence concerning safety, clinical effectiveness and costs.

MORE: Canadian first: Robotic single-site gallbladder removal

Given the for-profit health system in the USA, exciting new medical technologies are increasingly leveraged by hospitals to attract more business. The commercial nature of the system has led to reports that surgeons are being coerced by hospital administration to use da Vinci and concern of errors being made fueled the litigious faction into action. A closer look indicates that there is no specific concern about the inherent safety of the da Vinci surgical system, but rather the inadequate training of the surgeons employing this technology.

In Canada, we have a publicly-funded system with rationing of fixed health care resources. If a hospital acquires da Vinci technology in Canada it is at the behest of its surgeons who see this technology as an import investment in patient care. This has almost exclusively been made possible by the generosity of the donor communities. The absence of a commercial benefit to such technologies for Canadian health care providers creates a significantly different (and less controversial) dynamic here surrounding new medical technologies adopted by hospital surgeons. In both countries, the introduction of robotics is the latest in a continuum of care focused on improving the quality and safety of surgery through advances in technology. The evolution of minimally invasive surgery has allowed surgeons to harness the benefits of computer-assisted technologies to perform therapeutic interventions without the need for large incisions. This reduces pain and suffering and some complications.

The current scrutiny surrounding the introduction and expansion of robotic surgery is understandable – even healthy. It follows from a similar introduction of a disruptive technologic advance some thirty years ago that was new to the surgical community – laparoscopic “key-hole” surgery. Prior to this new procedure, a patient needing their gallbladder removed faced a painful abdominal incision accompanied by tubes, drains and a week or more in hospital. Today, with laparoscopic surgery, more than 80 per cent of gallbladder surgery is ambulatory care.

There is a cautionary tale to be heeded. Despite best efforts of surgeons to adapt, complication rates rose during the initial learning curve in the push to adopt this ”key-hole” approach which promised such tremendous benefits for patients. Understandably, accusations that this technology was being pushed by industry with inadequate surgeon training were prevalent. In fact, the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was once called ‘the biggest unaudited free-for-all in the history of surgery’.

Despite those early concerns, laparoscopic gallbladder surgery has become the standard of care and heralded the modern era of minimally invasive surgery. Today, various body cavity procedures from cardiac bypass to rectal cancer surgery can be performed with a minimally invasive approach. No one serious about providing quality care would turn the clock back now.

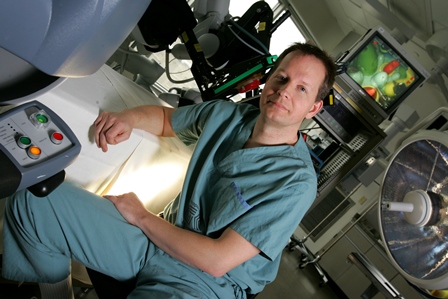

Robotic surgery carries the promise of advancing these technologic benefits even further. The da Vinci system provides enhanced instrument dexterity and offers full visual depth perception as compared to simple laparoscopic instruments. Surgeons who have embraced da Vinci do so in anticipation that it will lead to the next quality advance in patient care.

MORE:Robotic cancer surgery at CSTAR a Canadian first

In 1999, the London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) cardiac surgery team performed the world’s first closed-chest, off-pump, beating heart, coronary artery bypass surgery using the Zeus robot (Computer Motion). In 2003, the first da Vinci Surgical Systems (Intuitive Surgical) were put into service in Montreal Quebec and London Ontario. That year, 42 da Vinci procedures were performed at these two sites in Canada. By 2013, the 18 Canadian centres performing da Vinci surgery pushed that cumulative volume to over 10,000 cases.

Lessons from past adoption of new technologies inform our very rigorous approach to introducing this technology, including structured assessment of cost and patient outcomes.

The most commonly performed da Vinci procedure in Canada is radical prostatectomy, while hysterectomy is the fastest growing. Data as to the effectiveness of this unquestionably expensive technology is slow to come and occasionally conflicting.

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) performed a health technology assessment of robotic surgery to evaluate clinical and cost. In a review of 95 published articles on robotic surgery it was concluded that while the available data was of low quality, robotic surgery seemed to be generally associated with shorter hospital stay and reduced need for blood transfusions at the expense of longer operating time. The economic analysis demonstrated that the higher cost associated with robotic surgery is partially offset by reduction in hospital stay. Da Vinci surgery in Ontario is now the subject of a review by the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee of Health Quality Ontario.

Specifically with regard to the learning curve, it is key to consider what is the best comparator for robotic surgery. Published evidence, including our own laboratory research, suggests for a surgeon trained in open surgery, as compared to learning the laparoscopic approach, the learning curve for being able to offer patients a minimally invasive alternative is attenuated when da Vinci is employed. Surgeons can learn to use da Vinci faster than laparoscopic surgery.

In addition, the data does not support the negative outcomes being alleged in the media surrounding robotic surgery. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 peer-review studies comprising over 4,000 patients having robotic-assisted total hysterectomy versus open or laparoscopic surgery found the robotic approach was associated with a lower rate of complications. A study of a large administrative database looking at nearly 10,000 women having hysterectomy for benign disease found no differences in complications. In appropriately trained hands the da Vinci surgical system is safe.

By learning from the past, we have taken steps to ensure appropriate training precedes adoption of new approaches. At LHSC and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, since 2005 the Protocol and Guidelines for Robotic Surgery Innovation have been in effect. These guidelines lay out specific training criteria for surgeons wishing to adopt da Vinci technology and mandate clear disclosure requirements for obtaining informed consent from patients undergoing these procedures. In addition, every surgeon performing da Vinci surgery in London is tracking the outcomes of their cases and participating in a critical review of clinical and cost effectiveness of this technology.

MORE: Cardiac surgery world first: Complicated surgery simplified by new device

It is through this program that surgeons in London have reported 11 national and world firsts with da Vinci technology. As true leaders in robotic surgery innovation surgeons in London have also contributed to the safe introduction of this technology in other centres by acting as proctors and by having the Canadian Surgical Technologies and Advanced Robotics (CSTAR) program at LHSC designated the Canadian training centre for da Vinci surgery by Intuitive Surgical.

While questions still remain to be answered about the clinical and cost effectiveness of the current prevalent robotic surgery system, we are proud of the approach we have implemented for the introduction of this promising technology and will continue to evaluate its ongoing role in the Canadian health care system.