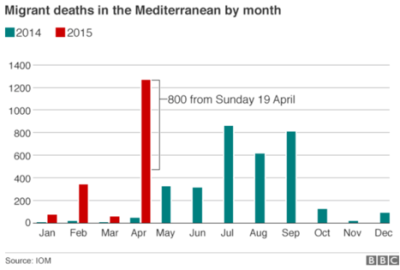

When Italy’s “Mare Nostrum” maritime #SAR (search-and-rescue) operation was terminated in November 2014, only a few Italian Coast Guard and passing merchant vessels remained as rescue resources for the deadliest refugee route in the world, the central Mediterranean from Libya to Italy.

True to form, #MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières / #Doctors Without Borders) had already decided to intervene, having had projects in many of these refugees’ countries of origin since years prior. The two per cent mortality rate on the central Mediterranean migrant route was also impossible to ignore. MSF’s Amsterdam office therefore negotiated a partnership with MOAS (Migrant Offshore Aid Station), to rescue and provide medical and humanitarian care for these “boat people”. MSF also intended to gather testimonies when possible and advocate for adequate SAR resources. This would be the first-ever ship-based MSF project, on a 40-meter fishing boat adapted for SAR work, the Phoenix.

This was also my first-ever MSF project, full of surprises despite an excellent preparation. Within 24 hours of setting sail on May 2nd we’d rescued 369 children, women, and men from one sinking wooden boat. After a long midnight pause to assist another 109 from an inflatable raft onto a nearby oil tanker, we headed north to Italy. In 28 repetitions of the same basic procedure over the summer of 2015, always according to the instructions of the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Rome, we plucked 6,985 people from grossly overcrowded and unseaworthy wooden boats and inflatable rafts. I learned much about the “migration crisis”, MSF, SAR techniques, and humanity.

We diagnosed and treated conditions ranging from minor injuries to fatal carbon monoxide poisoning. Skin abscesses and scabies were commonplace, due to unhygienic conditions in transit and in detention in Libya. People were universally exhausted and for the first several hours aboard would often sleep soundly on the metal deck, often only to later report that it was the best rest they’d had in months, or even years. Seasickness was the rule rather than the exception, and late effects of torture and trauma were not uncommon. After encountering cases of hypertensive emergency and testicular torsion I thought no presentation would surprise me.

I was truly astonished, therefore, to encounter a sick hemodialysis patient among those rescued. She’d had no treatments for three weeks since deciding to gamble her very last funds on the risky sea-passage, and was in trouble with shortness of breath, peripheral edema, and ominously tall peaked T-waves and dysrhythmia showing on our cardiac monitor. Intravenous calcium gluconate soothed her heart rhythm, followed by her helicopter evacuation to definitive care in Italy, which did much the same for mine.

Certain persistent memories remind me of priorities:

On the inspiring, brighter side: in May 2015 the European Union effectively reinstated the rescue resources of the summer of 2014, and many lives were consequently saved; a man with a broken knee healed at ninety degrees of flexion, after a truck accident in the Sahara that killed 23 others, was assisted by his companions for months. Whenever I’d catch his eye he’d flash a wide smile accompanied by an enthusiastic “thumbs-up” gesture. Another rescuee had spent months in summary detention in Libya, having no money to bribe himself out, and no relatives to forward any. He was slow to respond, had the bilateral lower-limb edema of the severely protein-malnourished, a hemoglobin level about one-third of normal, and a look of death about him. His compatriots passing through that place raised the cash to bail him out, onto the tragic boat from which we rescued them all.

Since my return home from the Mediterranean a few weeks ago there have been terrible killings in Beirut, Paris, and elsewhere, underscoring the urgent need for humanity, and not violence, to prevail. In the summer of 2015 our team on the Phoenix disembarked in Europe 6,877 women and men, and 108 clearly blameless persons below the age of five. I sincerely hope those children mature to enable a more humane world than exists today.