The human brain is the most complex organ in our body and unlike any other structure, the brain is what makes humans, human. The brain has many important functions such as storing memories, sending signals about feelings and emotions, enabling speech and movement and so much more.

The brain: A complex challenge

The unique and intricate structure of the human brain enables us to do many tasks, however, its complexity poses a challenge towards understanding, diagnosing and treating different brain disorders. Conditions that affect the brain such as ALS, Alzheimer’s disease and some cancers, can have devasting impacts on an individual, and given the complexity of the brain, are very difficult to treat.

In order to better understand the organization of the brain and disease progression, scientists depend on models that accurately represent the human brain. Currently, much of our scientific understanding of the brain is based on animal biology and while those models continue to play a valuable role in brain research, they remain limited because the human brain is dramatically different and unique from those of other animals.

Modelling the human brain

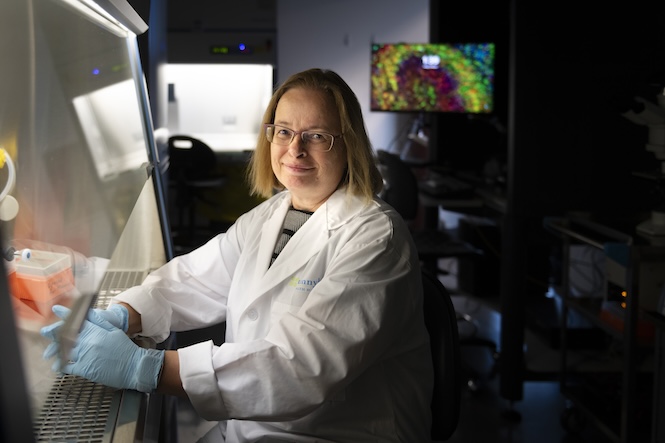

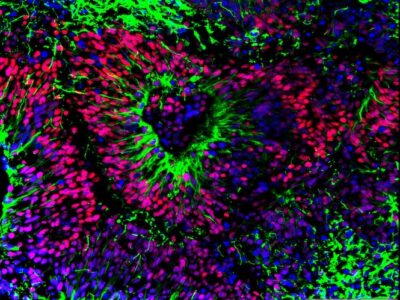

Scientists at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) are advancing the understanding of the human brain by developing models with more precision than ever before. Dr. Carol Schuurmans, senior scientist in the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program and Dixon Family Chair in Ophthalmology Research, leads Sunnybrook’s stem cell and organoid facility, which is managed by Dr. Dawn Zinyk. Dr. Schuurmans’ lab specializes in growing cerebral organoids, which are miniature and simplified versions of brain tissue, to better understand the cellular and molecular features of the human brain.

“We can use cerebral organoids to study many different things including developmental principles and disease mechanisms,” says Dr. Schuurmans. “Currently, these organoids are helping us understand which genes contribute to human brain development, with hopes of applying this tool to disease models to better recognize disease pathology and mechanisms.”

How are organoids designed?

Organoids are grown in vitro using pluripotent stem cells. Scientists isolate human blood or skin cells and convert them into pluripotent stem cells, which are cells that can give rise to and act as any one of the body’s more than 200 cell types. These stem cells are then mixed with a variety of molecules, which direct them to grow into different types of tissue, including brain tissue (i.e., cerebral organoids).

At SRI, scientists are currently growing organoids that resemble the neocortex, the front part of the brain that’s responsible for sensation and cognition. It can take three to four months to develop an organoid to a stage that models the cell composition of a human brain. At SRI, organoids have been grown for up to 10 months, where they become larger, more mature and increasingly complex.

What potential do organoids have for the future of brain health?

“The hope for these models is to support personalized medicine and treatments,” explains Dr. Schuurmans. “Using organoids, scientists and clinicians can observe disease progression in specific individuals, and with this knowledge, clinicians can determine the most effective course of treatment for that patient.”

Right now, scientists at SRI are growing cerebral organoids to study their potential to create personalized treatments for neurogenerative diseases like dementia. Possessing models that more accurately represent the unique and complex human brain will provide scientists with more effective tools to aid in advancing the future of brain health.

By Anna McClellan

Anna McClellan is a Communications Specialist, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.