By Vivian Sum

“People who come to us have symptoms so severe that they are not able to enjoy their life, work or relationships,” says Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute clinician-scientist Dr. Fidel Vila-Rodriguez.

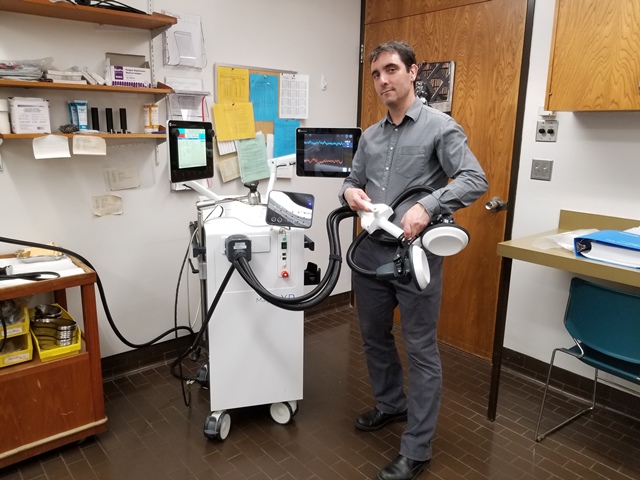

Vila-Rodriguez is leading the Vancouver arm of a clinical trial investigating magnetic seizure therapy (MST) to treat bipolar depression. The study—which is also recruiting patients in Toronto and London, Ontario—will compare the effectiveness and side effects of MST with the current electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) approach.

Results from the first randomized, double-blind study of its kind could lead to changes in how very severe cases of bipolar depression are treated.

“When we see patients, they have invariably already tried other treatments for their bipolar depression, such as psychotherapy and medications,” says Vila-Rodriguez.

Most patients are around 45 years of age and approximately 60 per cent are women. Many may be contemplating suicide or harming themselves in other ways, placing them in a life-threatening situation.

Around one percent of Canadians over 14 years of age will have symptoms of bipolar#1. In addition, around 700,000 Canadians were affected by treatment-resistant depression—when a patient does not respond to at least two antidepressants—in 2014.

ECT, which has been used since 1938, is shown to be one of the most effective therapies to put treatment-resistant depression into remission, with a reported 65 to 75 per cent success rate. However, a 2003 study published in the British Medical Journal found that at least one third of patients who underwent ECT reported persistent memory loss, which can deter some patients from pursuing this treatment.

Identifying the best therapy for treatment-resistant bipolar depression

While both ECT and MST induce minor seizures in the brain, patients are placed under general anesthesia to prevent body convulsions. Patients’ heart rate, level of blood oxygenation and blood pressure are all monitored during treatment. However, unlike ECT, MST uses magnetic currents, not direct electricity.

The seizures release neurotransmitters, such as adrenaline, dopamine and GABA—an inhibitory transmitter that stops the seizure. This process triggers neurogenesis, which produces new neurons in the brain.

“If this research shows that MST and ECT are similarly effective, but MST has fewer side effects, MST may quickly replace ECT as the preferred treatment.”

ECT and MST are part of a treatment mix for bipolar depression that includes psychotherapy and medication. And given its potential fewer side effects, MST could offer patients concerned about potential memory loss greater peace of mind.

“For some patients, this type of therapy is like flipping a switch,” says Vila-Rodriguez. “After a few sessions, their enjoyment of life, as well as their productivity, returns.”

Vivian Sum works in communications at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.