By Allan O’Dette

Even before the pandemic, patients in Ontario were waiting longer than they should for some surgeries and procedures.

When health-care resources were diverted to the COVID-19 response, wait times grew even longer and exacerbated the backlog that has ballooned to 21 million patient services including preventive care, cancer screenings, surgeries, immunizations, MRIs and more.

Doctors report that Ontarians have grown sicker and as they wait for the care they need, their outcomes are worse. The situation will become more severe as the unknown number of missing patients who didn’t get help during the pandemic seek treatment.

Ontario’s doctors have a solution, and we need the provincial government to act on it now so that patients can get the care they need.

First, invest in the resources required to clear the backlog. Then, set in motion the most significant modernization of surgical and procedural ambulatory care in 30 years to tackle wait times.

The Ontario Medical Association’s proposal is a significant system shift that involves moving patients who need less-complex surgeries and procedures away from overburdened hospitals and into ambulatory clinics.

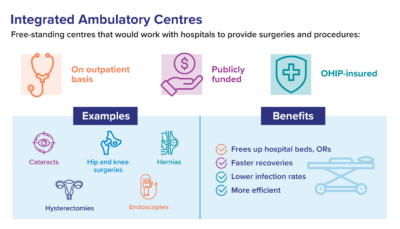

Integrated Ambulatory Centres — or IACs — would be free-standing centres working in partnership with hospitals to provide publicly funded, OHIP-insured surgeries and procedures safely and efficiently on an outpatient basis.

Cataract surgeries, for example, and those involving the ears, nose and throat. Hysterectomies and breast reconstructions after cancer. Procedures to treat hernias, gallbladders and prostrates. All could be done without a hospital stay.

Patients would get the care they need, and go home the same day.

Ambulatory centres provide surgery or procedure times that are shorter, with faster recovery and lower infection rates. They are 20 to 30 per cent more efficient.

Both patients and physicians would have a more satisfying experience. The modern and integrated system the OMA is recommending would allow for more collaboration by physicians, surgeons and specialists, something that benefits everyone.

Hospitals, in turn, would have increased capacity to perform more complex and urgent surgeries and procedures.

IACs would not violate the Canada Health Act because they would be fully integrated with the publicly funded health system. They would be subject to open and transparent public reporting and have strong clinical oversight.

As such, no one would jump the queue. There would be no two-tier service.

The evidence shows the system change we are proposing will work.

Ambulatory centres have been successful in other provinces such as Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C. Other countries that also have government funded universal health care have also demonstrated these clinics can perform a range of outpatient surgeries and procedures safely and efficiently. Ontario has dipped its toe in this water with the Kensington Eye Institute in Toronto.

When Saskatchewan Health compared the cost of performing 34 procedures in clinics and in hospitals, the results showed that in every case the clinics were less expensive. In some cases, they were half the cost.

A decade ago, the non-partisan Drummond Report recommended Ontario expand on the success of the Kensington Eye Institute. Yet, a recent Auditor General report found the province has made little progress in leveraging this model of care.

Instead, Ontario has not moved beyond the Independent Health Facility framework that is now more than three decades old.

The vast majority of the province’s nearly 1,000 IHFs are licensed for diagnostics such as X-rays and ultrasounds, with only a small minority licensed to deliver publicly funded surgeries or procedures. They were not built to handle the broad spectrum of surgeries and procedures that could move to IACs.

The vast majority of the province’s nearly 1,000 IHFs are licensed for diagnostics such as X-rays and ultrasounds, with only a small minority licensed to deliver publicly funded surgeries or procedures. They were not built to handle the broad spectrum of surgeries and procedures that could move to IACs.

Our solution will work only if we address the significant strain on health human resources, which has grown worse during COVID-19.

Having spent more than two years on the front lines of the pandemic, doctors, nurses and other health-care workers are burned out. Many are leaving the profession. Physicians who stay are bogged down in administrative burdens. They are overwhelmed by a provincial doctor-to-population ratio that is fourth from the bottom in OECD countries – if Ontario were counted as a country — and they are feeling the crush of a population that is growing and aging.

Fixing wait times and the backlog needs to start by supporting the people who are the core of health-care delivery systems. That means reducing red tape for physicians so they have more time for direct patient care. It means finding a way to measure and track burnout among health-care workers, and then taking action to address it.

If we can ensure we have the people we need in place and that those people have the physical and mental capacity to do what’s required, then we can begin to address the backlog and ensure no one waits longer than recommended guidelines for care.

The pandemic has shown us we need to re-think how care is delivered so we can take pressure off overburdened hospitals. COVID has shown us that the current model is simply not sustainable.

There is a clear path forward. We urge the government to take it.

Allan O’Dette is CEO, Ontario Medical Association.