By Sarah Garland

The diagnostic approach for pulmonary embolism (PE), a condition referred to as “The Great Masquerader,” is controversial. PE has earned its moniker because it is difficult to recognize and has symptoms that vary from patient to patient. Diagnosing it typically requires multiple steps, and the approach used can differ according to the resources at hand (e.g., staff to operate the machines and interpret the results). So let’s explore this — what exactly is PE, what do you do if you suspect a patient has PE, and what does the evidence say?

PE occurs when a blood clot, usually originating from the leg, travels and lodges in the arteries of the lung. However, the signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism — shortness of breath, feeling faint, chest pain, and cough — are not specific to only PE and could be attributed to many different conditions. This is part of the reason why PE can be difficult to diagnose, and determining the best strategy for diagnosis is so varied and complex. But it is also important that PE be diagnosed quickly, as the condition is a major cause of emergency hospitalization and, if left untreated, can be fatal in up to 30 per cent of patients.

The approach to diagnosing PE requires multiple steps, and the results of each test or exam helps determine the need for further testing. The initial step may be an assessment to determine the likelihood that a person has PE. Tests to help assess the likelihood or risk of a patient having PE are often referred to as clinical prediction rules; these provide a set of clinical criteria that can help determine if further testing is needed. Examples of these tests include the Wells rule, the Geneva score, and the revised Geneva score. Patients assessed to have a high probability of PE may proceed directly to diagnostic imaging, while patients with low probability may undergo further testing. These additional tests include Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria, also known as PERC, or D-dimer testing (a lab test that looks for indications in the blood that a patient has a blood clot). Based on the results of these tests, a patient may be referred for confirmation testing or be considered unlikely to have a PE and not require any further testing.

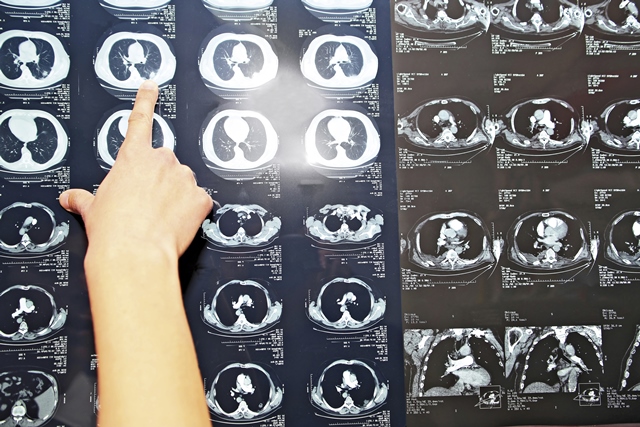

Patients who are deemed at high risk of PE following an initial assessment with a clinical prediction rule, or based on unstable presentation, usually undergo diagnostic imaging to confirm the disease. Previously, conventional pulmonary angiography had been considered the gold standard for PE imaging, but due to its invasive nature (i.e., it requires right heart catheterization), it has been overtaken by alternative imaging modalities. Less invasive methods for imaging include computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA), magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography (MRPA), ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scanning planar scintigraphy, V/Q single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or V/Q SPECT-CT, positron emission tomography–CT (PET-CT), and thoracic ultrasound. There are strengths and limitations to each of these modalities, and which one is appropriate may depend on several factors. Examples of these factors include the availability of the technology, the expertise and choice of the health care provider, contraindications (e.g., pregnancy or allergy to the contract dye used in CT), and considerations of radiation dose associated with the various modalities. Not all modalities are widely available or in routine clinical use in Canada. This may be due to a lack of availability or expertise, or due to practical considerations such as the increased time required and the complexity of performing the exam.

To help address the challenges associated with diagnosing adults with suspected PE, CADTH — an independent agency that finds, assesses, and summarizes the research on drugs, medical devices, tests, and procedures — conducted an evidence review of the various diagnostic approaches. The CADTH project assessed the diagnostic test accuracy, clinical utility, safety, cost-effectiveness, patient experiences and perspectives, implementation issues, ethical issues, and environmental impact. An expert panel, the Health Technology Expert Review Panel (HTERP), reviewed the evidence and developed recommendations.

Based on the evidence review, three key recommendations by HTERP emerged. These recommendations highlight different approaches for different patient populations; however, the use of the two-tiered model of the Wells rule is recommended as a first step for any adult with a suspected PE. Subsequent tests may be performed as necessary, and the need for diagnostic imaging is assessed after these tests. For the general population, the recommended pathway is two-tier Wells, followed by D-dimer if appropriate, and followed by CTPA if necessary. For the pregnant population, two-tier Wells followed by PERC and D-dimer testing (if appropriate) is recommended, followed by leg ultrasound and, if necessary, computed tomography pulmonary angiography. However, where there is a heightened concern about radiation exposure, and where the clinical situation allows, it would also be reasonable for the clinician and patient to undertake a shared decision-making process to select between CTPA and VQSPECT as the final step in the diagnostic pathway. Among patients for whom CT is strongly contraindicated, HTERP recommends two-tier Wells followed by D-dimer testing, followed by VQ-SPECT and, if necessary, leg ultrasound.

It should also be noted, in addition to patient characteristics, the available resources influence the choice of diagnostic imaging modality. To help determine availability of imaging machines, CADTH’s Canadian Medical Imaging Inventory was referenced and considered when developing the recommendations.

PE is recognized as a complex, nuanced condition, and the diagnostic approach will vary according to many contextual issues. There are different options and approaches when it comes to diagnosing PE, and CADTH evidence can help guide those decisions.

To learn more about our project on diagnosing PE, visit www.cadth.ca/PE or speak to a CADTH Liaison Officer in your region.

Sarah Garland is a Knowledge Mobilization Officer at CADTH and focuses on the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism.