By Tegan Slot

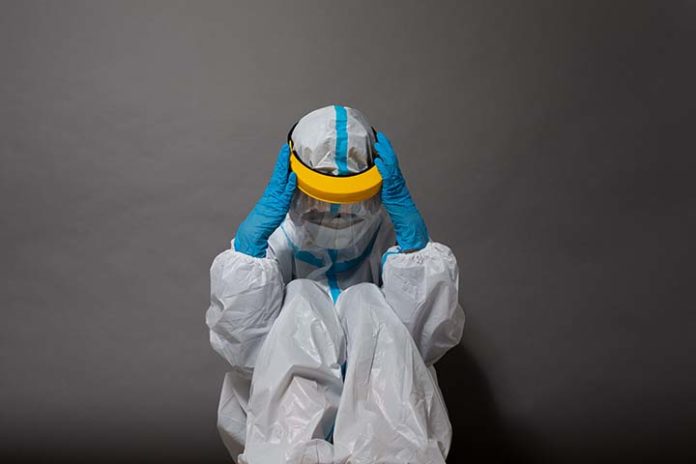

She’s a package wrapped neatly – tied tightly with a piece of string. Don’t ask her how she is – she’s fine. She’s fine because she has to be; she’s fine until she’s not. One more tug on the string that holds her together threatens to completely unravel her.

In June, a study by the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions on mental health disorder symptoms among nurses in Canada reported that 36 per cent of nurses screened positive for major depressive disorder, 29 per cent screened positive for generalized anxiety disorder and clinical burnout, 33 per cent reported having suicidal thoughts and 20 per cent screened positive for PTSD and panic disorders.

And that was before the COVID-19 pandemic substantially increased both the mental and physical demands on our frontline healthcare workers.

Katelyn* is a clinical care leader and has worked in emergency medicine and trauma units for the past 20 years of her nursing career. She hasn’t stopped in the past nine months, working at a grueling pace to keep up with workload demands. During the pandemic, hospitals are seeing increasing numbers of patients who are without primary care physicians and who no longer have access to the community mental health supports that they were dependent on. The number and type of patients seeking primary care through the hospital has grown – and so has the scope of care that Katelyn provides. Despite increased work demands, increased risk of exposure to a virus with potentially devastating health effects, and a fast-paced environment with ever-evolving provincial guidance on best practices to protect the physical safety of workers, Katelyn has maintained her baseline mental health. It wasn’t until she was required to support a local long-term care home – where a number of staff and residents tested positive for COVID-19 – that her mental health shifted. What changed that she could no longer maintain good mental health?

What factors are likely to cause mental-ill health in frontline healthcare workers and how do you know when to step back and seek help?

At the height of the first wave of the pandemic, Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers, in collaboration with the Institute for Work and Health, surveyed over 6000 workers on their experiences during the pandemic, with specific focus on mental health. Results show that roughly 43 per cent of respondents who had all their personal protective equipment (PPE) and Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) needs met reported symptoms of anxiety. When basic needs for protection of physical safety (PPE, IPAC) were not met, prevalence of symptoms of anxiety increased dramatically to over 60 per cent among respondents.

Protection of physical safety is only one area that contributes to symptoms of mental ill-health among healthcare workers. Other personal and work-related factors that impact mental wellbeing are:

- Heightened stress due to performing multiple roles or lack of role clarity

- Caring for patients in an increased state of reactivity

- Increased cognitive demands or mental load

- Working outside of professional scope

- Change in work hours

- Change in work environment

- Increased workload and unclear leadership expectations among others

- Decreased mental health supports

- Anxiety over uncertainty

- Being high-risk or caring for high-risk family members

- Multiple demands on working parents

- Reduced access to childcare

- Exposure to domestic violence

Workers exposed to any combination of these factors are at risk of experiencing mental ill-health which, according to the Canadian Armed Forces Mental Health Continuum model and the Mental Health Commission of Canada may be evidenced by:

- Feelings of fear, uncertainty, panic or anxiety

- Sleep disturbances and decreased state of physical health

- Increased difficulty with managing symptoms of chronic disease, chronic pain or disability

- Difficulty concentrating and becoming easily distracted

- Increased substance use (alcohol, gambling)

- Increased social isolation

- General changes in feelings and behaviours, such as increased anger, outbursts and suicidal thoughts.

What can the workplace do to protect and support the mental health of its workers? Hospital leadership are required to take every precaution reasonable under the circumstances to protect the health and safety of their workers. Traditionally, focus has been on the protection of the physical health and safety of workers. We’re now seeing more understanding, awareness, and focus on the importance of also protecting the psychological health of workers.

Most hospitals have a number of supports already in place for the protection of the mental health of their workers. Employee and Family assistance programs, incident reporting systems (both patient and employee), and return to work programs all have elements of psychological support embedded within. Yet, despite existing supports, workers continue to experience anxiety, depression, burnout, panic disorders and suicidal thoughts. So, what comes next?

Moving forward, the best starting point is to assess workplace needs. What type of exposures are workers experiencing? Chronic mental stress? Traumatic mental stress? What are the hospital’s areas of strength and areas of need with respect to psychosocial exposures? Once workplace needs are determined, supporting resources are accessed and implemented.

The most successful psychological health and safety programs with the greatest gains have strong leadership commitment, focus on leadership training, support for workers along the full mental health continuum (taking preventative measures to support mental health as opposed to a sole focus on intervention and recovery strategies once a mental health injury has occurred) and measure key leading and lagging performance indicators to track program successes.

Workplaces with a strong psychological health and safety program can expect to see a return on investment of $2.68 for every $1.00 spent after the first three years (Deloitte, 2018,). Having a strong psychological health and safety program in place that effectively supports healthcare workers’ mental health is also in the best interest of providing high quality patient care.

Public Services Health and Safety Association (PSHSA) – serving Ontario’s public services workplaces – has developed and provides consultation on a comprehensive psychological health and safety program to help workplaces identify, assess and control organizational and job-specific psychological factors affecting the mental health of frontline workers. PSHSA’s Psychological Health and Safety program resources include a checklist for employers to use as an initial gap analysis to determine what prevention, intervention and recovery measures are in place, whether they meet organizational needs, and to assist in future program planning, development and implementation for the protection of workers’ mental health (Figure 1).

Public Services Health and Safety Association (PSHSA) – serving Ontario’s public services workplaces – has developed and provides consultation on a comprehensive psychological health and safety program to help workplaces identify, assess and control organizational and job-specific psychological factors affecting the mental health of frontline workers. PSHSA’s Psychological Health and Safety program resources include a checklist for employers to use as an initial gap analysis to determine what prevention, intervention and recovery measures are in place, whether they meet organizational needs, and to assist in future program planning, development and implementation for the protection of workers’ mental health (Figure 1).

In addition to workplace resources, frontline workers who are experiencing mental ill-health during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond may wish to access community resources for mental health through the Mental health Commission of Canada’s Resource Hub.

Like Katelyn, thousands of Canadian nurses are grappling with the uncertainty of the pandemic. By augmenting current programming to protect the mental health of healthcare workers, hospital leadership can play a vital role in securing the proverbial string to ensure the package remains tightly bound.

*Katelyn is an pseudonym

Tegan Slot, R.Kin MSc PhD CRSP is a Health and Safety Consultant at the Public Services Health & Safety Association.