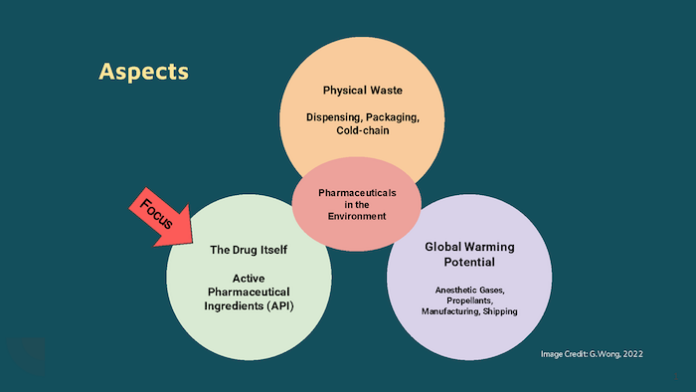

Typically, there are three main aspects brought up when considering pharmacy’s impact on planetary health: greenhouse gas emissions, physical waste, and pharmaceuticals impact as chemical contaminants that pose harm to wildlife. This article will specifically focus on the latter of the three.

There are three main aspects of pharmaceuticals in the environment.

The main pathway for drugs entering the environment is through human consumption, with excretions in urine and feces accounting for 88 percent. As these drugs containing the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) pass through the body, they may or may not be metabolized, and their metabolites can also have active effects. As these excretions make their way to wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), they are not always able to effectively remove pharmaceuticals, leading to their entry into our shared environment through water leaving the WWTP. As drug consumption increases, so do excretion rates, leading to more profound impacts. Remaining routes of entry into the environment include the disposal of expired, damaged, or unwanted medication making up ten per cent, and the remaining two per cent comes from manufacturing.

Drugs pose unique and concerning chemical risks as they are, by design, intended to cause a desired biological effect on the human body. As humans share a common physiology with other living things, some mechanisms of drug action effective in humans may also affect wildlife. This makes sense when considering the drug development process. In initial stages drugs are tested on mice, later cats and dogs, then non-human primates. Where a drug shows promise, it progresses to testing in humans. This is so logical yet is oddly and quietly alarming.

The first example of wildlife impacts is a story about birds – of three species of vultures in Southeast Asia. A staggering 99.9 percent of the population were dead in the devastating speed of 15 years. The culprit drugs? Diclofenac, a drug commonly used for both livestock and humans alike throughout Southeast Asia. As vultures are natural scavengers that feed on the carcasses of livestock, some of whom have been given this medication. This example may surprise readers, as diclofenac is widely used in Canada for pain, fever, and inflammation, available in various forms with or without prescription and belongs to a class of medication called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs.

A couple interesting things in this vulture story. First, is regarding the type of adverse effect. A well-known side effect of NSAIDs in humans is kidney failure (one to five percent). The vultures died from kidney failure too, with uric acid build-up leading to gout in the body cavities. Second relates to dose-response curves. You may be wondering what type of dose killed the birds? This might surprise you: when adjusted for weight in mg/kg, what is a five to ten percent of a therapeutic human dose is the 100 percent lethal dose in vultures. Indeed, a limitation and the point of this calculation is that diclofenac is processed differently in humans and vultures. This comparison is impactful as it illuminates how little is known about the dose-response curves of drugs in non-target organisms.

The second example of wildlife impacts focuses on flat-headed minnows. in freshwater lakes in Ontario. Researchers explored the effects of synthetic estrogen, common in birth control pills. Using concentrations that mimic those found in the environment in parts per trillion, they found that male fish became intersex and started producing eggs, there was a reduced ability of fertilized eggs to progress into offspring, and at the end of the seven year whole-lake experiment, the fish population was on the brink of extinction.

Perhaps this article will inspire action. Each of us can start today. A good starting point is to begin within your sphere of influence. Clinicians can use tools such as the climate-conscious Choosing Wisely Canada Recommendations on 20+ clinical specialties, weaving this together with a quality improvement for sustainable healthcare. Hospital pharmacies can explore ways to minimize preventable drug waste in its processes – an opportunity may be in medication returns being discarded instead of sorting for recirculation or exploring ways to better manage drug inventory with short dates. Supply chain leads can use our hospital procurement power in selection criteria of products and vendors. Executives and directors could embed this into their organization’s strategic plan, like Fraser Health Authority in Metro Vancouver, BC. Health-system leaders can also shape requirements for drug life cycle assessments to support more informed decisions.

By Gigi Y.C. Wong

Gigi Wong is a Clinical Pharmacy Specialist for the Fraser Health Authority as part of the Lower Mainland Pharmacy Services in Vancouver, BC.