By Neil Fraser

I have been working within the Canadian healthcare system for almost four decades and have witnessed the changing tides of health technology procurement. I’ve also seen countless reports on what we need to do to reform our healthcare system, and it is a rare treat to see those recommendations be put into action.

When I first started working within the healthcare system, adoption of a new technology was based on a doctor’s judgement that the technology could improve outcomes for their patients.

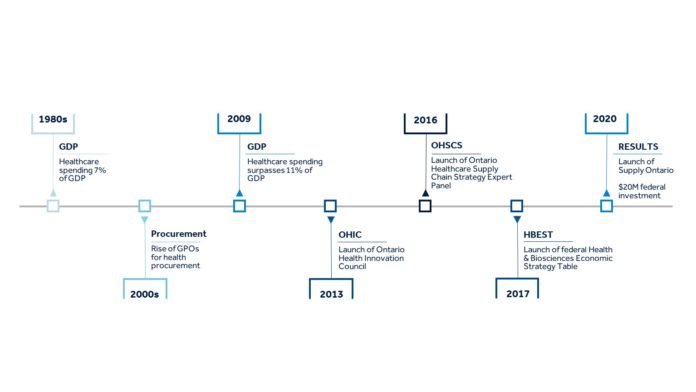

Over time, governments were finding themselves in deeper waters because healthcare costs – including capital, human resources, and pharmaceuticals – were representing a larger portion of GDP (from seven per cent in the 1980s to 11 per cent today). As a result, governments began focusing on reducing the growth in healthcare spending.

EMERGENCE OF CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT

In the mid-2000s, centralized procurement agencies began to emerge in earnest, with a specific focus on creating a more consistent and transparent procurement process, and success was measured by their ability to reduce the average price of medical products being procured.

It worked. Transparency increased. The procurement process became very complicated, but more consistent. And the price of some devices, like stents and pacemakers, plummeted. But despite the savings on devices, the overall cost of healthcare continued to rise.

The problem could be explained using basic math. Since medical devices only represent three-four per cent of healthcare spending, even if they were free, the system would only save four per cent at most. That is why considering the impact of devices on the total cost of care, including the other 96 per cent, is arguably more important. Furthermore, increasing the adoption of the right innovations could actually help the system support more patients without increasing overall costs or further burdening our human resources, which are already burning out.

In the 2010s, governments began to realize they had a health innovation problem and in 2013, Ontario was the first of several governments to develop health innovation councils. Two years later, the Ontario government accepted all the Ontario Health Innovation Council’s (OHIC) recommendations, which included the need to develop strategies to improve and coordinate the procurement, adoption and diffusion of innovative technologies across the entire health sector.

VALUE-BASED PROCUREMENT

In 2016, the Healthcare Sector Supply Chain Strategy (HSSCS) Expert Panel was put together and their top recommendation was also to form a single procurement agency in Ontario with the skills necessary to shift to value-based procurement. This meant that the procurement agency would be expected to give weight to patient outcomes with input from clinicians, to take resource utilization and the total cost of care into consideration, and focus on value, rather than just price.

That same year, Gabriela Prada of the Conference Board of Canada, and one of the experts on the HSSCS panel, published her paper “Value-Based Procurement: The New Imperative for Canada”. She argued that the criteria for tender evaluation should explicitly include patient outcomes and the total costs associated with the product being procured, including price, life cycle and total operating costs. (Full disclosure, Prada is now Senior Director of Global Health Systems Policy at Medtronic).

In Sweden, for example, Prada shared that procurement of wound-care products considered total care delivery costs for three different personas, rather than just the product itself. In Norway, procurement of IV catheters considered which products caused the least pain for patients and were least likely to break or require multiple attempts to administer.

In 2017, at the Healthcare Supply Chain Network, Kara LeBlanc from Shared Services New Brunswick presented her paper “Implementation Considerations for VBP in the Health Sector for New Brunswick, Canada”. While focused on New Brunswick, the key findings could be applied across Canada.

LeBlanc’s research identified that the factors important to the successful implementation of value-based procurement (VBP) include: “public procurement legislation reform, executive government directors and support, interest and support from stakeholders, and directives to conduct pilot projects. In addition, sound structures and support from multi-sector government representation, such as, physicians, health ministries, finance and economic development ministries, procurement/shared service organizations, and legal are important. Directives and support must come from the top down.”

I couldn’t agree more. VBP is integral to achieving the objectives of an innovation agenda. This was also one of the conclusions of the federal Health and Biosciences Economic Strategy Table in 2018, which also recommended funding sandboxes for innovative procurement that would “de-risk adoption of breakthrough Canadian health products”. This led to a $20 million investment in the CAN Health Network.

TIME TO SHINE

Fast forward to 2020 ― seven years after the OHIC recommendations, after the publication of several more papers on the topic of VPB, and with a new government ― the Ontario government created an integrated health supply chain organization called Supply Ontario. Its objectives including “drive innovation and emerging technologies” and “deliver greater value for taxpayer dollars”.

There has never been a more important time to leverage procurement to secure the supply of quality products that improve outcomes for patients and healthcare providers, given the global supply chain issues brought to light during the pandemic.

In particular, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of local production, as well as the need to partner with global suppliers. At the federal level, this challenge has now been passed on to the new Minster of Innovation, François-Philippe Champagne.

When the pandemic is over, and our healthcare system faces a tsunami of procedures delayed during the lockdown, my hope is that procurement, both provincial and federal, has its moment to shine by executing on the promise of procurement reform: procuring products that reduce procedure time, reduce readmissions, or keep patients out of the hospital altogether.

Neil Fraser is President of Medtronic Canada and he was a member of both the Ontario Health Innovation Council and the federal Advisory Panel for Healthcare Innovation. Editorial support provided by Melicent Lavers-Sailly, Director, Communications, Strategy, and Stakeholder Engagement.