For people who are in the intensive care unit (ICU) with a serious health condition, injury or recent major surgery, infections are a concern. Sometimes an infection is even what brought them into the hospital in the first place, like COVID-19. But any infection could lead to a life-threatening condition called sepsis.

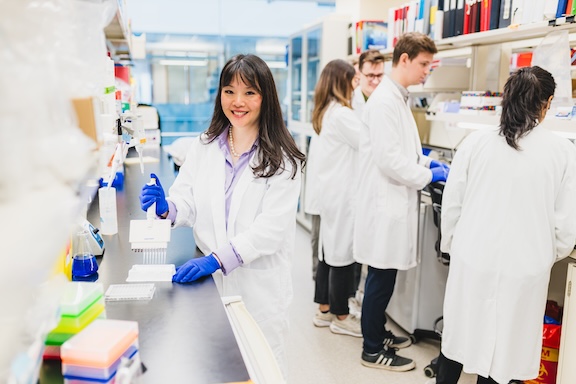

“When it comes to sepsis, the ultimate goal is to select the right treatment, at the right time, for the right patient,” says Dr. Patricia Liaw, a scientist at the Thrombosis & Atherosclerosis Research Institute (TaARI) of Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) and McMaster University. “There is no one-size-fits all treatment so it’s important to find alternative options that are effective for different types of sepsis patients.”

Liaw focuses her research on immunothrombosis, which is the process by which immune cells contribute to blood clotting in the presence of a severe infection. She is exploring a new treatment for patients with sepsis and is working closely with Dr. Alison Fox-Robichaud, an HHS critical care physician and national expert in sepsis, to ensure her work in the lab can translate well into a clinical setting.

Sepsis is caused when the body has an improper and aggressive response to an infection and is the leading cause of death worldwide. A type of immune cells called neutrophils respond to severe infections by releasing DNA into the blood stream which form sticky web-like structures. These structures can help trap and kill microorganisms, but they can also attach to blood cells and form blood clots. Since blood clots limit or block blood flow, this affects the supply of oxygen and nutrients that are delivered throughout the body. This can result in tissue damage, organ failure and death.

Breaking down the blood clots

Research from Liaw and her team have shown that some patients with severe sepsis have very high levels of circulating DNA in their blood, presumably released when the neutrophis encounter the infection. So, they conducted a multi-center study of 400 patients in the ICU with sepsis and found that patients with high levels of DNA in their blood have the poorest outcomes.

“If the sickest patients are likely to have the most blood clots, and blood thinners aren’t working at this stage, the drug we’re testing might be the answer.”

Liaw wondered if stopping the DNA from creating blood clots could be a solution. So, she’s found a drug that can do just that.

“We’re working on a Phase I clinical trial with a drug that breaks the connection between the sticky DNA structures and the blood cells, which essentially breaks down the blood clots,” says Liaw.

In early testing, Liaw and her team found the DNA-digesting drug to be most effective when sepsis is in advanced stages. Liaw says these preliminary findings are what make her clinical trial promising. “If the sickest patients are likely to have the most blood clots, and blood thinners aren’t working at this stage, the drug we’re testing might be the answer.”

Launching a clinical trial

Liaw and her team will begin the first phase of the trial in a few weeks. This is a safety and feasibility study which will recruit a small number of sepsis patients at HHS and

Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital in Montreal. This study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“In this first phase we’ll also determine the appropriate dose and duration of treatment and ensure that the process to administer the drug is realistic for the clinical staff,” says Liaw.

If this Phase 1 study has a successful outcome, the team will move on to a larger scale study to determine if the drug is effective.

Liaw strongly believes in ensuring there is a two-way bridge that connects lab-based research with applications that benefit patients. Her collaborations over the years with clinical colleagues such as Fox-Robichaud have helped to accelerate the translation of basic science discoveries to applications that improve human health. If this drug proves to be effective, she and her research team will continue to work to make it available to clinical teams at HHS. She’s hopeful that this treatment can help patients with life-threatening cases of sepsis not just in our community, but around the world.