By Eftyhia Helis

For the past two years, COVID-19 has taken over the world. It has made us mindful of viruses spreading through the air. It has taught us about the importance of public health measures and vaccines. It has brought “masks,” “isolation,” “contact tracing,” and “testing” into our common vocabulary.

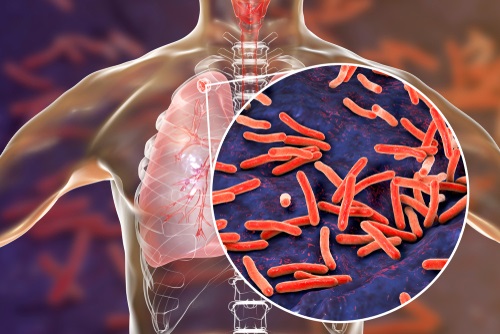

But another, similar infectious disease affects millions of people. Before COVID, it caused the highest number of deaths globally from an infectious disease. The disease is tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (TB) has been around for thousands of years. For many, TB might be an unknown disease or a disease that belongs to the past. However, for millions of people worldwide, TB is a reality. Although the incidence of TB in Canada is low, some populations are disproportionately affected. At the time of this article, there are TB outbreaks in at least 2 regions in Canada.

TB is often called “a social disease with medical dimensions,” highlighting the critical role that social conditions and health inequities play in its spread among vulnerable populations. While Canada and the global community have agreed to end TB by 2030, COVID has reversed any related progress. In this context, this year’s World TB Day on March 24 aims to highlight “the urgent need to invest resources to ramp up the fight against TB and achieve the commitments to end TB made by global leaders.”

CADTH – an independent, not-for-profit organization responsible for providing health care decision-makers with objective evidence to help make informed decisions about the optimal use of drugs, medical devices, tests, and procedures — identified TB as a topic of interest among several jurisdictions in Canada. Guided by input from TB stakeholders, CADTH reviewed the clinical evidence and guidelines on topics related to the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of TB. Below are some examples of evidence needs expressed by these stakeholders and related findings from the CADTH reviews.

TB Vaccines

Although more than 1 vaccine was quickly developed for COVID-19, there’s only 1 vaccine for TB. This vaccine, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), has been in use since 1921. In Canada, BCG is used for high-risk groups, including infants in communities with high risk of infection and those working in occupations with a higher risk of TB exposure (e.g., health care workers). Although this vaccine is widely used around the world, questions about its effectiveness and safety remain.

The available research suggests that, in people with healthy immune systems, the BCG vaccine is effective at preventing TB infection (protection ranged from 49% to 85%), including pulmonary TB (TB affecting the lungs). However, this research is limited, of low-quality, and might also be considered outdated. The protective effect of the vaccine may also diminish over time and information on possible side effects is limited because they are rarely reported and researched.

Screening Tests for Latent TB Infection

While the symptoms of active TB (persistent cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss) make it easy to diagnose, people with latent TB infection (when TB bacteria live in the body but are inactive) don’t have symptoms. Although people with latent TB infection (LTBI) can’t spread TB to others, LTBI has the potential to develop into active TB. That’s why LTBI screening and treatment is important.

To confirm if a person has LTBI, two tests are commonly used: a skin test (tuberculin skin test [TST]) or a blood test (interferon gamma release assay [IGRA]). IGRA appears to be more accurate in some populations (e.g., those vaccinated with BCG). However, it isn’t always available, particularly in rural and remote communities, because of infrastructure challenges for transporting the blood. Research on the use of IGRA for LTBI screening in rural and remote populations is also lacking.

Treatment Options

TB treatment consists of a combination of medications that are taken for 6 months or longer. Adherence to treatment for the entire duration is critical for curing the disease and preventing any remaining TB bacteria from becoming resistant to medications. Adherence to this strict treatment schedule is challenging for TB patients. Therefore, shorter treatment regimens have been suggested. Research into 4-month regimens for treating active TB suggests they may be as effective and safe as the 6-month regimen. The effectiveness of these shortened treatment regimens depends on the combination of drugs and the dose schedule.

Management Approaches

To improve treatment adherence, it’s recommended that people receive treatment in a clinic so they can be observed by a trained health professional while they’re taking their medications. This is called direct observational therapy (DOT). However, research suggests that DOT could be just as effective if provided by a family member and as effective or more effective when provided at home, at work, or in the community. Observing treatment remotely over a video connection also appears to be an effective alternative to DOT, if resources are available.

CADTH’s review found significant research gaps related to TB care. Because rates of TB, and the resources needed to control it, vary significantly across Canada, context-specific approaches are needed.

Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic could contribute to improved approaches for generating new research and supporting effective TB care in Canada and worldwide.

CADTH’s Repository of TB Evidence and Resources can be found at tuberculosis.cadth.ca. If you’d like to learn more about CADTH, visit cadth.ca, follow us on Twitter @CADTH_ACMTS, or speak to a Liaison Officer in your region: cadth.ca/Liaison-Officers.

Eftyhia Helis is a knowledge mobilization officer at CADTH.