York researchers simulated a C. difficile outbreak in a hospital ward. What they learned will capture the attention of public health officials, policy-makers, clinicians and epidemiologists.

By Megan Mueller

Clostridium Difficile, or C. difficile, strikes fear into the hearts of many. This life-threatening infection, caused through contact with bacteria, can develop rapidly even under the watchful eye of hospital staff. In fact, it is often spread in health care facilitates or nursing homes due to proximity of the bacteria.

Two researchers, Professor Seyed Moghadas and PhD student Sara Maghdoori, mathematicians in York University’s Agent-Based Modelling Laboratory in the Faculty of Science, wanted to evaluate strategies for reducing this risk. Their research, funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) ̶ which identifies one of its top research priorities as health and related life sciences and technologies ̶ and the Mathematics of Information Technology and Complex Systems (Mitacs), considered how to control C. difficile in hospitals and offered new hope through early detection – more specifically: screening.

Sara Maghdoori

“Rapid detection remains an important component of control. Screening in-hospital patients with potential exposure to colonized patients or contaminated environment and equipment can help reduce the rates of transmission,” says Maghdoori, the lead author. (Moghadas co-authored and supervised.) “Colonization” refers to the development of a bacterial infection in a patient. The infected person may have no signs or symptoms of infection while still having the potential to infect others.

“This will have significant public health and clinical implications, especially in light of the emergence and community spread of hypervirulent strains of C. difficile,” Moghadas adds. Policy-makers, public health officials, clinicians and epidemiologists will be interested in these findings, published in BMC Infectious Diseases (2017).

C. difficile among top 10 infectious causes of death in the developed world

C. difficile is one of the most common infections found in hospitals and long-term care facilities. Moghadas and Maghdoori report that C. difficile has become the leading cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea worldwide, and it remains among the top 10 infectious causes of death in the developed world.

Seniors in health care facilities are at greatest risk, as are people with other illnesses or conditions being treated with antibiotics and certain other stomach medications that increase the risk of C. difficile colonization.

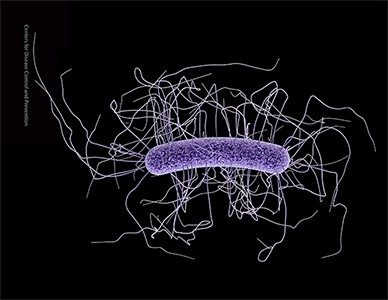

Medical illustration of C. difficile. Source: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

The most common symptom of C. difficile is diarrhea, which can lead to serious complications, including dehydration and colitis. Other symptoms include fever, loss of appetite, nausea and abdominal pain. In rare cases – those involving antibiotic-associated colitis, bowel perforation and sepsis, which can occur when the body’s response to infection causes injury to its own tissues – it can be fatal (Government of Canada). A 2010 report produced by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and the Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion found that C. difficile caused more premature death than other hospital-acquired infections.

For those experiencing mild symptoms, no treatment is needed. Others may need antibiotic. In these cases, the symptoms usually clear up after the cycle of antibiotics is completed. In severe cases, medication and even surgery may be needed.

How many Canadians develop C. difficile and what does this cost the system?

According to one 2015 Canadian study, published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases, there were 38,000 cases in Canada in 2012. This costs the health care system an estimated $280 million annually. Over 90 per cent of this ($260 million) was in-hospital costs, over four per cent ($12 million) was direct medical costs and four per cent ($10 million) was due to lost productivity, so says the study. Relapses are costly as well: Management of relapses alone accounted for $65 million, or 23 per cent.

Two facts about C. difficile are quite disturbing: incidences are increasing, and there are hypervirulent strains of C. difficile. Both underscore the need for improved control measures.

Research finds transmission can happen even without carrier patients on ward

It was these changing conditions that inspired Maghdoori and Moghadas to consider more effective control measures. But first they needed to know more about transmission. To do this, they launched a study that used a simulation model for the transmission of C. difficile in a hospital ward based on previously published estimates.

The researchers ran the simulation for 200 days, and were able to pinpoint transmission either through asymptomatic carriers or as a result of ineffective implementation of infection control practices. The diagram below illustrates the dynamics of infection and patient screening in the study.

The dynamics of infection and patient screening in the study

“The results show that, for a sufficiently high transmissibility of C. difficile, the disease can persist in a hospital through in-ward transmission, even when there are no other asymptomatically colonized patients (or unknowing carrier patients) at the time of hospital admission,” Moghadas explains.

Screening can help reduce rates of silent transmission

The research team concluded that screening of in-hospital patients with potential exposure to colonized patients or contaminated environment and equipment can help reduce the rates of silent transmission of C. difficile through asymptomatic carriers.

“This is particularly important as a recent study, published by JAMA Intern Med, highlights the importance of indirect transmission, where the receipt of antibiotics by prior hospital bed occupants can increase the risk of C. difficile in subsequent patients occupying the same bed,” Moghadas explains.

The article, “Assessing the effect of patient screening and isolation on curtailing Clostridium difficile infection in hospital settings,” was published in BMC Infectious Diseases (2017). The 2010 ICES/Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion report is available online. The 2016 article published in JAMA Intern Med, “Receipt of Antibiotics in Hospitalized Patients and Risk for Clostridium difficile Infection in Subsequent Patients Who Occupy the Same Bed,” is also available. To learn more about Moghadas, visit his faculty profile.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch, watch the York Research Impact Story and see the snapshot infographic.

Megan Mueller is manager, research communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca