A recent late-night Emergency Department shift was like many others. I saw patients of all ages and a broad range of medical issues. As I reflect back, two patients stood out.

Both were elderly men with serious complex chronic conditions. But one was fortunate enough to be accompanied by family members, whereas the other arrived by ambulance alone. In the first case, the man’s wife and daughter helped communicate his health issues because he didn’t speak English. They brought his recent medical records and were a comforting presence over a period of several hours. Their participation in his care helped make it possible for me to send him home in accordance with his wishes. Without similar help, the other man spent several hours alone as we tried to piece together what was happening; he was admitted to the hospital though he had hoped to go home.

It struck me how much difference can be made by the presence of family and friends. Yet these critical caregivers are rarely acknowledged when we talk about the health system.

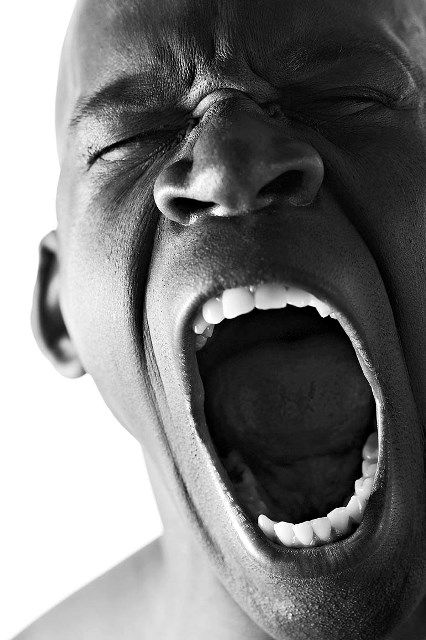

Chances are most of us have acted as informal, unpaid caregivers at some point for a parent, child or spouse. When we serve in this role, we provide critical support to our loved ones and the health system at large. However, this support often comes at a personal cost, especially when caregiving stretches into months or even years. During that late-night shift, the man’s daughter spoke urgently about wanting to stay with her father, but also needing to return home to her kids and be ready for other commitments the next morning. Visibly distressed, she was torn between duties to different parts of her life.

Health Quality Ontario has released a new report to better understand distress like this, among unpaid caregivers of long-stay home care patients in Ontario. We found rates of stress, anger and depression have more than doubled for these caregivers, climbing from 15.6 per cent to 33.3 per cent between 2009/10 and 2013/14.

Within that time frame, long-stay home care patients cared for by family members or friends have also become collectively more cognitively impaired, more functionally disabled and sicker.

In Ontario, at least one informal caregiver, such as a spouse or adult child, shoulders the everyday care of almost all long-stay home care patients (97 per cent) who also receive publicly funded home care. Most assume the role with little to no formal training, stepping in to fill the hours not covered by a paid support worker.

For many informal caregivers, time-intensive caregiving can lead to sleepless nights, emotional exhaustion and feelings of guilt or loneliness that may negatively impact their lives. Some studies associate long-term caregiving with physical problems, such as back aches, migraines, stomach ulcers, hormonal changes and even early death.

Our report also shares stories from families across Ontario. Nghi is a former trading supervisor for a stock brokerage, who must decide between returning to work and selling his home in order to pay bills related to informal caregiving for his mother. Carole Ann stood by her husband Bill throughout his five-year ordeal of nine ankle surgeries, many infections and congestive heart failure. “Bill’s wounds have healed,” she says. “But I don’t think I have.”

Watching someone we care about suffer from prolonged illness or declining health is always difficult, so it’s not possible to completely eliminate distress. However caregivers should not have to endure avoidable stress.

Caregivers are an integral part of our health system. It’s critical that we support them in times when they support others.