Since its inception, the St. Michael’s Hospital emergency department has responded to many mass-casualty events – treating patients injured in tragic shootings, to massive parades, to highway car crashes.

This tradition of saving lives in the most challenging circumstances goes back decades, with one particular event standing out amongst the others.

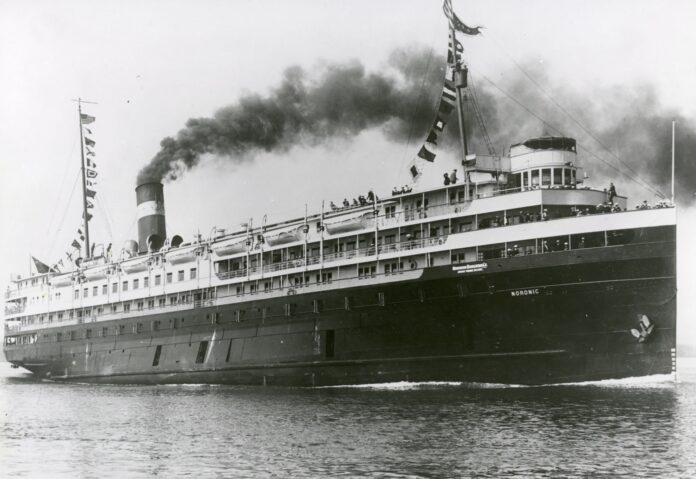

On the night of Sept. 16, 1949, the Canadian steamship The S.S. Noronic was docked in Toronto Harbour as part of a seven-day pleasure cruise of Lake Ontario. But in the early morning hours of Sept. 17, a fire broke out on the steamship, spreading quickly and resulting in the deaths of roughly 120 passengers.

Injured and burned victims of the fire were sent to St. Michael’s Hospital and Toronto General Hospital, with between 70 and 80 patients arriving at St. Michael’s for treatment starting at around 3 a.m. The hospital called in doctors and nurses who worked overnight, and well into the next day, to treat the wounded. The Sisters of St. Joseph, who founded the hospital, set up a call centre to notify family members of patients being treated and handed out blankets to people waiting.

Lenore, who has asked to be referred to by first name only, was a nurse in the St. Michael’s Hospital emergency department at the time of the S.S. Noronic fire.

“It was a very quiet evening,” says Lenore, who was a graduate of the nursing school that used to operate out of St. Michael’s. “And then all of a sudden there were sirens from everywhere and patients from everywhere.”

The immediate treatment of patients from the fire included bandaging, anti-tetanus serum, morphine and penicillin, according to an article in Canadian Hospital from the time, with some requiring minor and major surgery. Large quantities of blood plasma were also needed throughout the course of the night and following day.

The night of the S.S. Noronic fire, a physician named Dr. Paul McGoey was on duty. McGoey was no stranger to a disastrous fire. As outlined in the St. Michael’s Nursing Alumnae News after the event, McGoey had been a part of the response to the Coconut Grove fire in Boston about five years earlier which resulted in more than 200 deaths. This experience may have helped him to guide the emergency department through the chaos of the S.S. Noronic disaster.

Lenore says the response to the disaster was inspiring. Clinical staff who were not on shift that night – and some doctors who did not work at the hospital at all – came in to assist with the influx of patients, and many others stayed well beyond the normal hours of their shifts. Patients, many of whom were badly burned, patiently waited for their turn to be treated – recognizing that those around them were in worse condition.

“Toronto responded 100 per cent to this tragedy,” Lenore says.

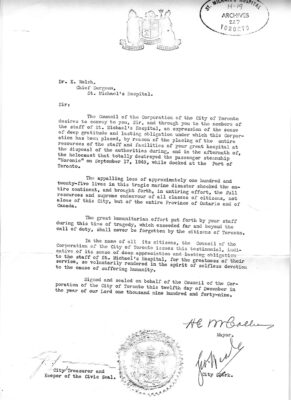

The fire and its aftermath were covered by major news outlets like the Toronto Star, and the City of Toronto even sent a letter of thanks to St. Michael’s for its quick and efficient response to the disaster. Many passengers of the S.S. Noronic were American, and their family members reached out to thank the Canadian hospitals that responded to the tragedy for their incredible care.

Lessons learned for today

Dr. Carolyn Snider, an emergency physician and researcher at St. Michael’s, says the S.S. Noronic fire is a historical reminder of the need for constant learning and education about how to best respond to a crisis.

The emergency and trauma teams at St. Michael’s, which are made up of many departments and roles, regularly practice for Code Orange mass casualty events, even bringing in simulated patients and partnering with Toronto Police Services to make the scenarios as realistic as possible.

Snider says that while no hospital wants to have to be good at handling a catastrophic event, the reality is that St. Michael’s is very good at it.

Lenore says she’s enjoyed reading about recent work being done at St. Michael’s, particularly the work of the emergency department and trauma centre, in the years since she left.

When asked what she learned from the S.S. Noronic event, Lenore says that staying positive is key.

“I think we must not become a little discouraged. That old saying ‘better to light one little candle’ is true. Sometimes you can think it isn’t going to make any difference. But it does.” n